COVID-19: An Interactive Analysis

A new virus has plauged us and caused turmoil in the world. This virus has caused shut-downs, lockdowns and in the worst-case will unfortunately cause deaths. It is our job as responsible citizens to do our best to stop it from further spreading, and what better way than for us data scientists to dive deep into the data (of course while wearing masks and keeping the safe distance). So lets dive in.

Introduction

The SARS-CoV-2 virus causes Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19), an infectious respiratory disease. The majority of those infected with the virus will have mild to moderate respiratory symptoms and will recover without the need for medical attention. Some, on the other hand, will become critically unwell and require medical assistance. Serious sickness is more likely to strike the elderly and those with underlying medical disorders such as cardiovascular disease, diabetes, chronic respiratory disease, or cancer. COVID-19 can make anyone sick and cause them to get very ill or die at any age.

But how does the virus spread?

Coughing, sneezing, and talking are the most common ways for the virus to spread through small droplets. Although the droplets are not normally airborne, persons who are in close proximity to them may inhale them and become infected. By contacting a contaminated surface and subsequently touching their face, people can become sick. Aerosols that can stay suspended in the air for prolonged periods of time in confined places may also be a source of transmission. It is most contagious in the first three days after symptoms develop, but it can also spread before symptoms appear and from asymptomatic people. Which strongly explains the value of wearing well fitted masks and as further illustrated in the GIF below.

So if we ask ourselves how can we prevent COVID-19 from spreading, we’ll find these main precautions to take:

- Keep a safe distance away from somebody coughing or sneezing.

- When physical separation isn’t possible, wear a mask.

- Seek medical help if you have a fever, cough, or difficulty breathing.

- If you’re sick, stay at home.

- Hands should be washed frequently. Use soap and water or an alcohol-based hand rub to clean your hands.

- Keep your hands away from your eyes, nose, and mouth.

- When you cough or sneeze, cover your nose and mouth with your bent elbow or a tissue.

How is the virus detected?

Real-time reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (rRT-PCR) from a nasopharyngeal swab is the usual method of diagnosis. Although chest CT imaging may be useful for diagnosis in patients with a strong suspicion of infection based on symptoms and risk factors, it is not recommended for routine use screening (Wikipedia), which may present an option to utilize computer vision for example by using convolutional neural networks to detect the virus in CT image scans, we’ll explore this another time in a different article.

Diving Deep into the data

All these previous precautions mentioned are of tremendous importance to stop the virus from further spreading but these won’t allow us to study more concisely where it spreads, why it spreads in areas more than others and how we can flatten the curve, as they are proactive measures, we are trying to analyze the historical (even though the virus is still fairly young) data through reactive measures of data analysis and machine learning, of course proactive (unsupervised learning) measures can also be deployed. That’s where data analysis comes into play. I dug deep into the data and all the accompaying code in this article can be found in this Github repository: Covid-19-Analysis.

The data is provided by John Hopkins University, it is available in their Github repo. The data is updated daily. I will also be using data from Our World In Data and acaps for further data exploration.

Lets start by first importing all required libraries. And setting some default settings

|

|

I’ll be using plotly for interactive plotting. ipywidgets for interactive user data filtering and selection. Pandas and numpy for data manipulation. scikit-learn for machine learning and further corresponding libraries for other utilities.

We’ll then load the datasets using Pandas straight from the source URL, because in this way everytime the code is ran it will have the most up to date data, rather than a downloaded Excel or CSV file.

|

|

Shape for Statistics DataFrame: (167554, 34)

Shape for Measures DataFrame: (23923, 18)

Shape for Confirmed DataFrame: (284, 783)

Shape for Deaths DataFrame: (284, 783)

Shape for Recovories DataFrame: (269, 783)

After loading the data and printing their shapes I had a quick look at it using several Pandas DataFrame methods such as,

head, sample , describe and info. I then grouped each case status by Country/Region which I will use later.

|

|

Due to the shape of the data (see above; dates are columns), I created a combined dataframe for easier manipulation, analysis and visualization.

|

|

I then created a figure, a Tree Map to be precise to get the latest world-wide Covid-19 status data. The figure was produced using plotlys graph_objects API, which has support for many different types of figures (TreeMap in this example,using the general Figure)

|

|

Just a quick side note, you might realize that the recovery data is odd, as there is this sudden plummet on the 5th of August 2021. This is because this data has been discontinued from that day onwards (here is the issue: Recovery data to be discountinued)

I have added this figure for illustration on how plotly works in general but all other interactive plots have been deployed to Binder and Heroku using voila. These can be attractive deployment options for machine learning apps and/or interactive dashboard apps for analysis (I will be using them quite often in the future 😊). The links for the interactive dashboard are:

Both apps are using Voila as an interface to make the notebook interactive so there isn’t any difference in how the app looks (see demo video below). The app will take a bit of time to launch as it has to execute all code cells in the notebook, some which take a bit longer due to creating animations in the figure (as we’ll see later 😉). So be patient and you’ll be able to interact with the figures, you can continue reading in the meantime.

Ok I hope you got the dashboard app up and running, now moving on. The next analysis I decided to conduct is to get the daily change in Covid-19 cases per status, which are either “Confirmed”, “Recovored”, “Active” or “Deaths”. This figure is produced with this piece of code below:

|

|

The figure this time is produced using the FigureWidget object instead, to be able to have interactions with ipywidgets, as we will see below. The y-axis is produced by utilizing the index column, and to use it in the apply function, as an index (duh) to compute the daily difference in cases for each status. I am also using ipywidgets as mentioned above for interactive user data filtering and selection, in this case only to filter the date of the figures (but many more in the dashboard app). This can be done by adding a SelectionRangeSlider widget that outputs a tuple of dates (the start and end date). These dates can then be an input to the function update_axes which updates (guess what?) the axes. Plotlys figures have a very convenient function named batch_update, which according to the documentation, is “A context manager that batches up trace and layout assignment operations into a singe plotly_update message that is executed when the context exits." So I have used it as well to update the figure based on the user selected dates. Finally this is wrapped in an interactive output using ipywidgets interactive_output function to get the interactive figure. All the interactive graphs that have these selection/filtering figures are produced using the same workflow.

- First create a figure

- Then create the widgets (adding options from the data/figure)

- Writing the update logic in a callable function

- Finally wrapping the widgets, update logic and figure in a final output widget.

I have added several other interactive figures in the dashboard app that I will not discuss here. But you can definitely check out the code for them in the Github repository linked above, and interact with the figures in the app also linked above.

The next analysis I wanted to work on is trying to predict the number of cases per status (Confirmed, Recovered, Active, Deaths). I opted for Linear regression to conduct such analysis. If you haven’t read my blog post on linear regression read it here. The blog posts tries to cover most of the details of linear regression, but also includes polynomial regression, which is linear regression with polynomial features, It’s also possible to think of it as a linear regression with a feature space mapping (aka a polynomial kernel). I will try to dedicate a seperate post for polynomial features and polynomial regression, but all you need to know ahead here is that the time series data of the Covid-19 cases is not linear, it can have various shapes, particularly for the daily changes per status data, the others are fairly linear especially the ‘Confirmed’ and ‘Deaths’, but of course they are if we are looking at the cumulative count, as seen below (click the ‘Confirmed’ or ‘Deaths’ button). But if you look at the daily changes data (also by clicking their respective buttons), it is not that linear.

The code below shows how Polynomial Regression can be done using scikit-learns PolynomialFeatures

|

|

Best Polynomial Degree for feature 'Confirmed' is 9

Best Polynomial Degree for feature 'Deaths' is 1

Best Polynomial Degree for feature 'Recovered' is 2

Best Polynomial Degree for feature 'Active' is 4

Best Polynomial Degree for feature 'Confirmed Daily Change' is 8

Best Polynomial Degree for feature 'Deaths Daily Change' is 7

Best Polynomial Degree for feature 'Recovered Daily Change' is 3

Best Polynomial Degree for feature 'Active Daily Change' is 2

First I added the daily change to the dataframe and then I computed our input feature which is the days. After that we simply run a for loop to try different degrees of Polynomials for the different Covid-19 status. The results for the best Polynomial per status are printed, the results are obtained by finding the lowest Mean Squared Error and finally the prediction results are added to a dataframe (df_prediction) for visualization.

|

|

The results may not look so great. But it did a fairly good job for a quick implementation, other methods might perform much better for example a recurrent neural network with LSTM or GRU layers, or even a 1-dimensional convolutional neural network. These options might be better for time-series data such as Covid-19 cases. XGBoost, or other ensemble boosted methods can also perform very well on time series data. Given that good feature engineering is conducted to get lagging/leading values, rolling averages etc. (I will write about these different topics in a seperate blog post)

I also created a World Map using plotlys Choropleth figure object, to get the status stats per country in a map. I also added an interactive figure with widgets to get different Covid-19 rates per country and filter by dates. I then used plotly to create animations to visualize the development of Covid-19 cases for the top 20 countries with the highest number of cases. All these figures can be found in the app linked above.

The final analysis I conducted was to see if a measure introduced by the government to reduce/limit the number of Covid-19 infection is effective or not. As I am living in Germany I only did this analysis for Germany, but it can of course be reproduced for other countries as well.

|

|

Firstly, I filtered the datasets just for Germany (as mentioned), had a look at the data types and data in general, removed unnecessary columns, dropped NA rows and finally merged the two datasets for analysis.

|

|

I wanted to get the week of Covid-19 since its start to add to the dataframe for further analysis as we will see later. I didn’t want the week of the year, but that can also be used if conducting the analysis for just one year, but I want this analysis to be reproducible anytime it is ran, maybe if the virus is still here after several years, hopefully not (UPDATE: It is still here after 2 years 😕), then the analysis would still be feasible and it is done with this piece of code:

|

|

I first used the pairwise function to get consecutive pairs of weeks for example, Week 1 and 2, Week 2 and 3, Week 3 and 4 etc.

I then got the first and last dates in the dataframe to create a weekly date range using Pandas date_range and with frequency W-MON, which is weekly every Monday. This week range is then used to create a dictionary that maps these weeks to their number since the start of Covid. Finally we loop through these pairs of weeks and check if the date is between these pairs of weeks then we assign it the week number of the start week.

We can then get the average of new or total cases per week for Germany by doing this

|

|

We can then see these sudden rises and falls of new cases in certain weeks, we will try to see why. I chose only a subset of measures to analyse which I think are the mostly employed measures, these are:

- Schools closure,

- Limit public gatherings

- Isolation and quarantine policies

- Visa restrictions

- Closure of businesses and public services

I then added (annotated) when these measures where first introduced to the previous plot:

|

|

And luckily with plotly you can slightly zoom in to see when these measures where first introduced. When they were first introduced only the Visa Restrictions measure had weeks after it with a decreased average of new cases.

Next I did a naive analysis to see if the measures mentioned are effective or not. This is done by looking at the average of new cases 4 weeks before the measure was introduced and the average of new cases 4 week after the measure was introduced (for everytime it was introduced/employed). This method has a flaw which we will discuss in just a second but first lets see how we can do that:

|

|

We can then see the results below and that the out of these 5 measures 3 were effective, Schools closure, Visa restrictions and Closure of businesses and public services. But like I said above this analysis has a flaw because even if the rise has already occurred, a countermeasure is usually implemented in response to it. If the measure was implemented during a period of rapid growth in new infections and only took effect after 4 weeks, it is evident that the number of new infections 4 weeks before the measure was implemented will be lower than the number of new infections 4 weeks after it was implemented.

| MEASURE | Average Infection 4 weeks Before | Average Infection 4 weeks After | Effective | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | Schools closure | 34754.687500 | 26264.750000 | 1 |

| 1 | Limit public gatherings | 24231.833333 | 31325.944444 | 0 |

| 2 | Isolation and quarantine policies | 12751.886364 | 23022.522727 | 0 |

| 3 | Visa restrictions | 18329.333333 | 17110.750000 | 1 |

| 4 | Closure of businesses and public services | 23464.150000 | 23450.275000 | 1 |

With that being said we know from Linear Regression that it is trying to estimate the coefficients of the input variables, these coefficients help us determine the relationship between the input variable (independent variable/predictor/feature) and the output variable (dependent variable/response/target). So I have used Linear Regression to estimate the coefficient for the ’effectiveness’ of the measure as we will see below.

|

|

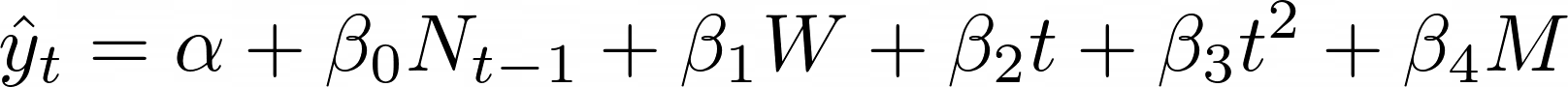

I first get the average new cases per week and reindex them to calculate the weekly trend in average new cases by substracting subsequent weeks from previous weeks. I have also used the Week and Week squared as input features as well. Finally the input feature we are mostly interested in, is the measure feature which is different for every measure hence the different input variables ( X_<measure>) for the different measures. This will give us this Linear Regression equation:

Where:

- $ {\alpha} $ is the y-intercept

- $ {\beta}_{i} $ is for the coefficients to be estimated

- $ N_{t-1} $ is for the new infections 1 week ago

- $ W $ is for the weekly trend $ (N_{t-1} – N_{t-2}) $

- $ t $ is for the week

- $ t^2 $ is for the week squared

- $ M $ is for the measure dummy variable

Then how can we interpret this coefficient? It is fairly simple, we can interpret this coefficient by its sign if it is negative then it is reducing the weekly average of new cases, if it positive it is either not reducing it or the average is still on the rise. Here are the results:

|

|

Schools Closure Coefficient: -136.60953972008906

Limit public gatherings Coefficient: 178.78724726294902

Isolation and quarantine policies: 272.8940135554292

Visa restrictions Coefficient: -574.2499316102472

Closure of businesses and public services Coefficient: -97.1873527294096

And coincidently the naive approach had the same results as the Linear Regression approach the same 3 measures are effective here as well.

We can also use statsmodels to estimate the coefficients like so:

|

|

We add a constant to get the intercept of the Linear Regression ($ {\alpha} $), the results are very similar to scikit-learns LinearRegression class which uses scipys linalg.lstsq in the backend.

Thank you very much for reading all the way through, and I hope you enjoyed the article and hopefully we can all defeat this virus together, don’t forget to check out the interactive dashboard app linked above. You can of course write me if you have any questions or just want to chat :), all my contact details are at the end of the page. See you in the next article and, Stay Safe!