Logistic Regression: With Application and Analysis on the 'Rain in Australia' Dataset

Introduction

The logistic model (or logit model) in statistics is a statistical model that represents the probability of an event occurring by making the log-odds for the event a linear combination of one or more independent variables.

Logistic regression is another approach borrowed from statistics by machine learning. It is the go-to strategy for binary classification problems (problems with two classes) even though it is a regression algorithm (predicts probabilities, more on that later).

For example,

- To predict whether an email is spam (1) or not (0)

- Whether the tumor is malignant (1) or not (0)

This post will discuss the logistic regression algorithm for machine learning.

What’s the Problem with Linear Regression for Classification?

The linear regression model is effective for regression but ineffective for classification. Why is this the case? If you have two classes, you may label one with 0 and the other with 1 and use linear regression. It works technically, and most linear model programmes will generate weights for you. However, there are a couple issues with this approach:

- A linear model does not produce probabilities, but rather treats the classes as integers (0 and 1) and finds the optimum hyperplane (for a single feature, a line) that minimises the distances between the points and the hyperplane. As a result, it just interpolates between the points and cannot be interpreted as probabilities.

- A linear model will also extrapolate numbers below zero and above one. This is a promising hint that there may be a more intelligent method to classification.

- Linear models are not applicable to multi-class classification issues. The next class would have to be labelled with 2, then 3, and so on. Although the classes may not be in any meaningful order, the linear model would impose an odd structure on the relationship between the features and your class predictions. The higher the value of a positive-weighted feature, the more it contributes to the prediction of a class with a higher number, even if classes with similar numbers are not closer than other classes.

Because the predicted outcome is a linear interpolation between points rather than a probability, there is no meaningful threshold at which one class can be distinguished from the other. A decent example of this problem may be seen on Stackoverflow.

So what can be a solution to classification problems, well there are many but one solution is logistic regression, here come the logistic function (or the sigmoid function)

The Logistic Function

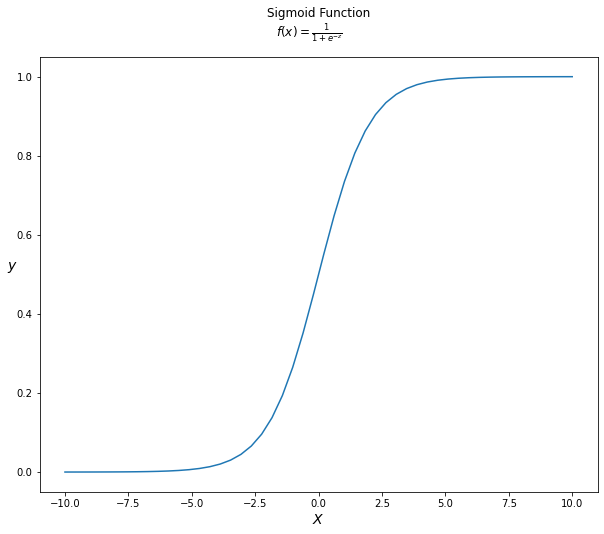

Logistic regression is named after the logistic function, which is at the heart of the algorithm. The logistic function, also known as the sigmoid function, was devised by statisticians to characterise the characteristics of rapid population expansion in ecology that exceeds the carrying capacity of the ecosystem (check here). It’s an S-shaped curve that can transfer any real-valued integer to a value between 0 and 1, but never exactly between those bounds. $$f(z) = \frac{1}{1 + e^{-z}}$$

Where $e$ is the natural logarithm base (Euler’s number) and z is the actual numerical value to be transformed.

Below we can see the logistic/sigmoid function applied to a range of numbers between -10 and 10 transformed into the range 0 and 1 using the logistic function.

Now that we’ve defined the logistic function, let’s look at how it’s employed in logistic regression.

Logistic Regression Algorithm Representation

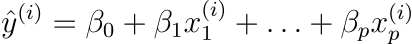

Logistic regression, like linear regression, uses an equation as its representation. The transition from linear regression to logistic regression is rather simple. We used a linear equation to model the link between the outcome and the features in the linear regression model:

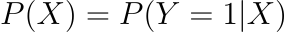

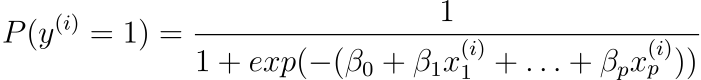

We prefer probabilities between 0 and 1 for classification, so we wrap the right side of the equation in the logistic function. This constrains the output to only accept values between 0 and 1.

To predict the output value ($y$), the input values ($X$) are linearly combined using weights or coefficient values (referred to as the Greek capital letter Beta). The coefficients in the equation are the real representation of the model that you would store in memory or in a file.

Why Logistic Regression is Regression not Classification

Simply put, logistic regression predicts probabilities which are continous values (i.e., regression).The probability of the default class is modelled using logistic regression (e.g. the first class). For example, if we are modelling people’s gender based on their height as male or female, the first class may be male, and the logistic regression model could be expressed as the probability of male given a person’s height, or more formally:

In other words, we are modelling the probability that an input (X) belongs to the default class (Y=1); we can express this formally as:

Logistic regression is a linear method, however the logistic function is used to alter the predictions. As a result, we can no longer understand the predictions as a linear combination of the inputs, as we can with linear regression. To continue from above, the model can be described as:

We can transform the previous equation as follows (remembering that we may eliminate the $e$ (exp) from one side by adding a natural logarithm ($ln$) to the other):

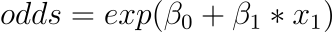

This is beneficial because we can see that the output on the right is linear again (exactly like linear regression), and the input on the left is a log of the likelihood of the default class. This ratio on the left is known as the default class’s odds (it’s historical that we use odds rather than probabilities; for example, odds are used in boxing rather than probabilities). Odds are calculated as a ratio of the event’s likelihood divided by the event’s probability of not occurring. For example, 0.5/(1-0.5) which has the odds of 1. So we could instead write:

Because the odds are log transformed, the left hand side is referred to as the log-odds or the probit. Although different types of functions can be used for the transform, the transform that relates the linear regression equation to the probabilities is commonly referred to as the link function, for example, the probit link function.

We can reposition the exponent to the right and write it as:

All of this helps us understand that the model is still a linear combination of the inputs, but that this linear combination is related to the default class’s log-odds.

Learning the Logistic Regression Model Parameters

The logistic regression algorithm’s coefficients must be estimated using your training data. This is typically accomplished through the use of maximum-likelihood estimation (gradient-descent can also be used, article on that in the future)

Although it does make assumptions about the distribution of your data, maximum-likelihood estimation (MLE) is a frequent learning method utilised by a variety of machine learning algorithms.

The best coefficients would result in a model that predicted a value very close to 1 (for example, male) for the default class and a value very close to 0 (for example, female) for the other class. The idea behind maximum-likelihood logistic regression is that a search algorithm seeks coefficient values that minimise the error (see The loss function) between the probabilities predicted by the model and those in the data (e.g. probability of 1 if the data is the primary class). It is sufficient to state that a minimization algorithm is utilised to optimise the coefficient values for the training data.

The loss function and MLE

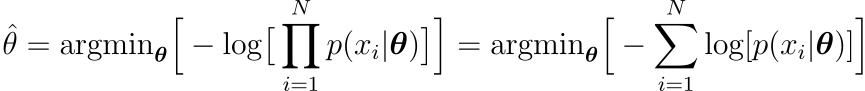

So, to learn the coefficients ($\beta$) of a logistic regression model, we need to define a cost function. MLE is a specific type of probability model estimation, where the loss/objective function is the log likelihood (or minimizing the negative log likelihood) denoted by $\mathcal{L}$.

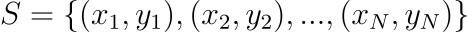

Suppose we have a set of experimental observations:

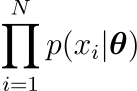

and a class of distributions $p(x;\theta)$, where $\theta$ is a set of parameters on which the form of $p$ depends. The MLE for the distribution from which the dataset has been extracted is defined as the one which maximizes the quantity

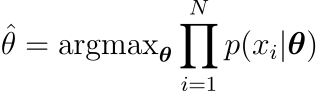

as $\theta$ varies. Therefore, in the hypothesis that variables are i.i.d. (Independent and identically distributed) the best value for $\theta$ will be given by

Because multiplication easily overflows/underflows, the equivalent expression is frequently used instead of this one

Let’s look at how this method can be used to construct the log-likelihood loss function (also known as cross-entropy).

Surprisingly, while training machine learning algorithms, the maximum likelihood estimation method can be used to create loss functions. In fact, one can imagine working in a scenario in which a dataset with specific statistical qualities is generated, and then construct a loss function that takes those properties into account automatically.

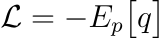

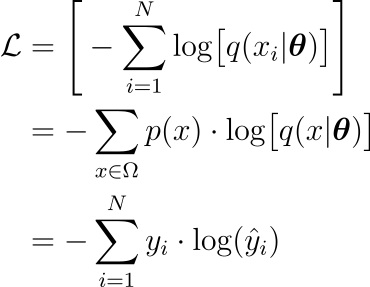

Log likelihood or cross-entropy is the mainly used loss function in classification problems, namely problems in which the underlying distribution has a discrete set of output values. Just as an example one can imagine a Bernoulli distribution, which has two outputs, one having probability $p$ and the other $(1−p)$ of being extracted. The negative log likelihood is defined as

and in information theory it quantifies the average number of bits needed to identify an event drawn from a set if a coding scheme used for the set is optimized for an estimated probability distribution $q$, rather than the true distribution $p$. This quantity can also be derived using MLE. Suppose data extracted according to a distribution $p(x)$ and an estimated distribution $q(x)$. Let’s also define the class of estimated probability distributions $\hat{y} = \hat{g}(x; \vec{\theta})$. Then the optimal parameters are obtained minimizing

where $\Omega$ is the sample space on which the probability space is defined. This way negative log likelihood is recovered as well.

Prediction with Logistic Regression

Predictions with a logistic regression model are as easy as plugging numbers into the logistic regression equation and computing the result.

Let’s put this into context with an example. Imagine that we had a model that can determine a person’s gender based on their height (completely fictitious). Is the person male or female given a height of 192cm?

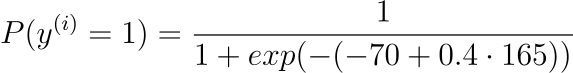

Assuming we now know (learned) the coefficients $\beta_{0} = -70$ and $\beta_{1} = 0.4$. Using the aforementioned equation, we can determine the probability of a male given a height of 165cm, or $P(male|height=165)$.

Or a very low probability of that the person is a male.

In practise, the probabilities can be used immediately. Because this is a classification problem and we want a useful result, we can convert the probabilities to a binary class value, such as

Using Logistic Regression on a dataset

I’ll be using the Rain In Australia dataset found in kaggle. The dataset contains information regarding daily weather measurements from a variety of sites in Australia and the aim is to predict whether it will rain the next day or not (Yes or No), which is a binary classification problem that is well suited for logistic regression.

I implemented Logistic Regression with Python and Scikit-Learn using its LogisticRegression class. All code can be found in my github.

I first import the libraries and load the dataset.

|

|

Then I conduct some Exploratory Data Analysis (EDA), some cleaning and data preparation for modelling

Dataset shape

|

|

(145460, 23)

Preview the dataset

|

|

| Date | Location | MinTemp | MaxTemp | Rainfall | Evaporation | Sunshine | WindGustDir | WindGustSpeed | WindDir9am | ... | Humidity9am | Humidity3pm | Pressure9am | Pressure3pm | Cloud9am | Cloud3pm | Temp9am | Temp3pm | RainToday | RainTomorrow | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 2008-12-01 | Albury | 13.4 | 22.9 | 0.6 | NaN | NaN | W | 44.0 | W | ... | 71.0 | 22.0 | 1007.7 | 1007.1 | 8.0 | NaN | 16.9 | 21.8 | No | No |

| 1 | 2008-12-02 | Albury | 7.4 | 25.1 | 0.0 | NaN | NaN | WNW | 44.0 | NNW | ... | 44.0 | 25.0 | 1010.6 | 1007.8 | NaN | NaN | 17.2 | 24.3 | No | No |

| 2 | 2008-12-03 | Albury | 12.9 | 25.7 | 0.0 | NaN | NaN | WSW | 46.0 | W | ... | 38.0 | 30.0 | 1007.6 | 1008.7 | NaN | 2.0 | 21.0 | 23.2 | No | No |

| 3 | 2008-12-04 | Albury | 9.2 | 28.0 | 0.0 | NaN | NaN | NE | 24.0 | SE | ... | 45.0 | 16.0 | 1017.6 | 1012.8 | NaN | NaN | 18.1 | 26.5 | No | No |

| 4 | 2008-12-05 | Albury | 17.5 | 32.3 | 1.0 | NaN | NaN | W | 41.0 | ENE | ... | 82.0 | 33.0 | 1010.8 | 1006.0 | 7.0 | 8.0 | 17.8 | 29.7 | No | No |

5 rows × 23 columns

Get column names

|

|

Date, Location, MinTemp, MaxTemp, Rainfall, Evaporation, Sunshine, WindGustDir,

WindGustSpeed, WindDir9am, WindDir3pm, WindSpeed9am, WindSpeed3pm,

Humidity9am, Humidity3pm, Pressure9am, Pressure3pm, Cloud9am, Cloud3pm,

Temp9am, Temp3pm, RainToday, RainTomorrow

View summary of dataset

|

|

<class 'pandas.core.frame.DataFrame'>

RangeIndex: 145460 entries, 0 to 145459

Data columns (total 23 columns):

# Column Non-Null Count Dtype

--- ------ -------------- -----

0 Date 145460 non-null object

1 Location 145460 non-null object

2 MinTemp 143975 non-null float64

3 MaxTemp 144199 non-null float64

4 Rainfall 142199 non-null float64

5 Evaporation 82670 non-null float64

6 Sunshine 75625 non-null float64

7 WindGustDir 135134 non-null object

8 WindGustSpeed 135197 non-null float64

9 WindDir9am 134894 non-null object

10 WindDir3pm 141232 non-null object

11 WindSpeed9am 143693 non-null float64

12 WindSpeed3pm 142398 non-null float64

13 Humidity9am 142806 non-null float64

14 Humidity3pm 140953 non-null float64

15 Pressure9am 130395 non-null float64

16 Pressure3pm 130432 non-null float64

17 Cloud9am 89572 non-null float64

18 Cloud3pm 86102 non-null float64

19 Temp9am 143693 non-null float64

20 Temp3pm 141851 non-null float64

21 RainToday 142199 non-null object

22 RainTomorrow 142193 non-null object

dtypes: float64(16), object(7)

memory usage: 25.5+ MB

- We can see that the dataset contains mixture of categorical and numerical variables.

- Categorical variables have data type object.

- Numerical variables have data type float64.

- Also, there are some missing values in the dataset. We will explore it later.

View statistical properties of dataset

|

|

| MinTemp | MaxTemp | Rainfall | Evaporation | Sunshine | WindGustSpeed | WindSpeed9am | WindSpeed3pm | Humidity9am | Humidity3pm | Pressure9am | Pressure3pm | Cloud9am | Cloud3pm | Temp9am | Temp3pm | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| count | 143975.000000 | 144199.000000 | 142199.000000 | 82670.000000 | 75625.000000 | 135197.000000 | 143693.000000 | 142398.000000 | 142806.000000 | 140953.000000 | 130395.00000 | 130432.000000 | 89572.000000 | 86102.000000 | 143693.000000 | 141851.00000 |

| mean | 12.194034 | 23.221348 | 2.360918 | 5.468232 | 7.611178 | 40.035230 | 14.043426 | 18.662657 | 68.880831 | 51.539116 | 1017.64994 | 1015.255889 | 4.447461 | 4.509930 | 16.990631 | 21.68339 |

| std | 6.398495 | 7.119049 | 8.478060 | 4.193704 | 3.785483 | 13.607062 | 8.915375 | 8.809800 | 19.029164 | 20.795902 | 7.10653 | 7.037414 | 2.887159 | 2.720357 | 6.488753 | 6.93665 |

| min | -8.500000 | -4.800000 | 0.000000 | 0.000000 | 0.000000 | 6.000000 | 0.000000 | 0.000000 | 0.000000 | 0.000000 | 980.50000 | 977.100000 | 0.000000 | 0.000000 | -7.200000 | -5.40000 |

| 25% | 7.600000 | 17.900000 | 0.000000 | 2.600000 | 4.800000 | 31.000000 | 7.000000 | 13.000000 | 57.000000 | 37.000000 | 1012.90000 | 1010.400000 | 1.000000 | 2.000000 | 12.300000 | 16.60000 |

| 50% | 12.000000 | 22.600000 | 0.000000 | 4.800000 | 8.400000 | 39.000000 | 13.000000 | 19.000000 | 70.000000 | 52.000000 | 1017.60000 | 1015.200000 | 5.000000 | 5.000000 | 16.700000 | 21.10000 |

| 75% | 16.900000 | 28.200000 | 0.800000 | 7.400000 | 10.600000 | 48.000000 | 19.000000 | 24.000000 | 83.000000 | 66.000000 | 1022.40000 | 1020.000000 | 7.000000 | 7.000000 | 21.600000 | 26.40000 |

| max | 33.900000 | 48.100000 | 371.000000 | 145.000000 | 14.500000 | 135.000000 | 130.000000 | 87.000000 | 100.000000 | 100.000000 | 1041.00000 | 1039.600000 | 9.000000 | 9.000000 | 40.200000 | 46.70000 |

Univariate Analysis

Explore RainTomorrow target variable

|

|

3267

|

|

|

|

2

['No' 'Yes']

As expected only 2 values (Yes or No)

|

|

No 110316

Yes 31877

Name: RainTomorrow, dtype: int64

No 0.775819

Yes 0.224181

Name: RainTomorrow, dtype: float64

We see an unbalanced problem

|

|

Findings of Univariate Analysis

- The number of unique values in RainTomorrow variable is 2.

- The two unique values are No and Yes.

- Out of the total number of RainTomorrow values, No appears 77.58% times and Yes appears 22.42% times.

Bivariate Analysis

Types of variables

In this section, I segregate the dataset into categorical and numerical variables. There are a mixture of categorical and numerical variables in the dataset. Categorical variables have data type object. Numerical variables have data type float64.

First of all, I will find categorical variables.

|

|

There are 7 categorical variables

The categorical variables are : ['Date', 'Location', 'WindGustDir',

'WindDir9am', 'WindDir3pm', 'RainToday', 'RainTomorrow']

|

|

| Date | Location | WindGustDir | WindDir9am | WindDir3pm | RainToday | RainTomorrow | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 2008-12-01 | Albury | W | W | WNW | No | No |

| 1 | 2008-12-02 | Albury | WNW | NNW | WSW | No | No |

| 2 | 2008-12-03 | Albury | WSW | W | WSW | No | No |

| 3 | 2008-12-04 | Albury | NE | SE | E | No | No |

| 4 | 2008-12-05 | Albury | W | ENE | NW | No | No |

Summary of categorical variables

- There is a date variable. It is denoted by Date column.

- There are 6 categorical variables. These are given by Location, WindGustDir, WindDir9am, WindDir3pm, RainToday and RainTomorrow.

- There are two binary categorical variables - RainToday and RainTomorrow.

- RainTomorrow is the target variable

Explore problems within categorical variables

First, I will explore the categorical variables.

|

|

Date 0

Location 0

WindGustDir 9330

WindDir9am 10013

WindDir3pm 3778

RainToday 1406

RainTomorrow 0

dtype: int64

|

|

WindGustDir 9330

WindDir9am 10013

WindDir3pm 3778

RainToday 1406

dtype: int64

We can see that there are only 4 categorical variables in the dataset which contains missing values. These are WindGustDir, WindDir9am, WindDir3pm and RainToday

|

|

Location

Canberra 3418

Sydney 3337

Perth 3193

Darwin 3192

Hobart 3188

Brisbane 3161

Adelaide 3090

Bendigo 3034

Townsville 3033

AliceSprings 3031

MountGambier 3030

Launceston 3028

Ballarat 3028

Albany 3016

Albury 3011

PerthAirport 3009

MelbourneAirport 3009

Mildura 3007

SydneyAirport 3005

Nuriootpa 3002

Sale 3000

Watsonia 2999

Tuggeranong 2998

Portland 2996

Woomera 2990

Cairns 2988

Cobar 2988

Wollongong 2983

GoldCoast 2980

WaggaWagga 2976

Penrith 2964

NorfolkIsland 2964

SalmonGums 2955

Newcastle 2955

CoffsHarbour 2953

Witchcliffe 2952

Richmond 2951

Dartmoor 2943

NorahHead 2929

BadgerysCreek 2928

MountGinini 2907

Moree 2854

Walpole 2819

PearceRAAF 2762

Williamtown 2553

Melbourne 2435

Nhil 1569

Katherine 1559

Uluru 1521

Name: Location, dtype: int64

WindGustDir

W 9780

SE 9309

E 9071

N 9033

SSE 8993

S 8949

WSW 8901

SW 8797

SSW 8610

WNW 8066

NW 8003

ENE 7992

ESE 7305

NE 7060

NNW 6561

NNE 6433

Name: WindGustDir, dtype: int64

WindDir9am

N 11393

SE 9162

E 9024

SSE 8966

NW 8552

S 8493

W 8260

SW 8237

NNE 7948

NNW 7840

ENE 7735

ESE 7558

NE 7527

SSW 7448

WNW 7194

WSW 6843

Name: WindDir9am, dtype: int64

WindDir3pm

SE 10663

W 9911

S 9598

WSW 9329

SW 9182

SSE 9142

N 8667

WNW 8656

NW 8468

ESE 8382

E 8342

NE 8164

SSW 8010

NNW 7733

ENE 7724

NNE 6444

Name: WindDir3pm, dtype: int64

RainToday

No 109332

Yes 31455

Name: RainToday, dtype: int64

RainTomorrow

No 110316

Yes 31877

Name: RainTomorrow, dtype: int64

|

|

Date contains 3436 labels

Location contains 49 labels

WindGustDir contains 17 labels

WindDir9am contains 17 labels

WindDir3pm contains 17 labels

RainToday contains 3 labels

RainTomorrow contains 2 labels

We can see that there is a Date variable which needs to be preprocessed. I will do preprocessing in the following section.

All the other variables contain relatively smaller number of variables.

Feature Engineering of Date Variable

|

|

Explore Numerical Variables

|

|

There are 19 numerical variables

The numerical variables are : ['MinTemp', 'MaxTemp', 'Rainfall', 'Evaporation',

'Sunshine', 'WindGustSpeed', 'WindSpeed9am', 'WindSpeed3pm', 'Humidity9am', 'Humidity3pm',

'Pressure9am', 'Pressure3pm', 'Cloud9am', 'Cloud3pm', 'Temp9am', 'Temp3pm', 'Year', 'Month',

'Day']

|

|

| MinTemp | MaxTemp | Rainfall | Evaporation | Sunshine | WindGustSpeed | WindSpeed9am | WindSpeed3pm | Humidity9am | Humidity3pm | Pressure9am | Pressure3pm | Cloud9am | Cloud3pm | Temp9am | Temp3pm | Year | Month | Day | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 13.4 | 22.9 | 0.6 | NaN | NaN | 44.0 | 20.0 | 24.0 | 71.0 | 22.0 | 1007.7 | 1007.1 | 8.0 | NaN | 16.9 | 21.8 | 2008 | 12 | 1 |

| 1 | 7.4 | 25.1 | 0.0 | NaN | NaN | 44.0 | 4.0 | 22.0 | 44.0 | 25.0 | 1010.6 | 1007.8 | NaN | NaN | 17.2 | 24.3 | 2008 | 12 | 2 |

| 2 | 12.9 | 25.7 | 0.0 | NaN | NaN | 46.0 | 19.0 | 26.0 | 38.0 | 30.0 | 1007.6 | 1008.7 | NaN | 2.0 | 21.0 | 23.2 | 2008 | 12 | 3 |

| 3 | 9.2 | 28.0 | 0.0 | NaN | NaN | 24.0 | 11.0 | 9.0 | 45.0 | 16.0 | 1017.6 | 1012.8 | NaN | NaN | 18.1 | 26.5 | 2008 | 12 | 4 |

| 4 | 17.5 | 32.3 | 1.0 | NaN | NaN | 41.0 | 7.0 | 20.0 | 82.0 | 33.0 | 1010.8 | 1006.0 | 7.0 | 8.0 | 17.8 | 29.7 | 2008 | 12 | 5 |

Summary of numerical variables

- There are 16 numerical variables.

- These are given by MinTemp, MaxTemp, Rainfall, Evaporation, Sunshine, WindGustSpeed, WindSpeed9am, WindSpeed3pm, Humidity9am, Humidity3pm, Pressure9am, Pressure3pm, Cloud9am, Cloud3pm, Temp9am and Temp3pm.

- All of the numerical variables are of continuous type

Explore problems within numerical variables

|

|

MinTemp 637

MaxTemp 322

Rainfall 1406

Evaporation 60843

Sunshine 67816

WindGustSpeed 9270

WindSpeed9am 1348

WindSpeed3pm 2630

Humidity9am 1774

Humidity3pm 3610

Pressure9am 14014

Pressure3pm 13981

Cloud9am 53657

Cloud3pm 57094

Temp9am 904

Temp3pm 2726

Year 0

Month 0

Day 0

dtype: int64

We can see that all the 16 numerical variables contain missing values.

Outliers in numerical variables

|

|

MinTemp MaxTemp Rainfall Evaporation Sunshine WindGustSpeed \

count 141556.0 141871.0 140787.0 81350.0 74377.0 132923.0

mean 12.0 23.0 2.0 5.0 8.0 40.0

std 6.0 7.0 8.0 4.0 4.0 14.0

min -8.0 -5.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 6.0

25% 8.0 18.0 0.0 3.0 5.0 31.0

50% 12.0 23.0 0.0 5.0 8.0 39.0

75% 17.0 28.0 1.0 7.0 11.0 48.0

max 34.0 48.0 371.0 145.0 14.0 135.0

WindSpeed9am WindSpeed3pm Humidity9am Humidity3pm Pressure9am \

count 140845.0 139563.0 140419.0 138583.0 128179.0

mean 14.0 19.0 69.0 51.0 1018.0

std 9.0 9.0 19.0 21.0 7.0

min 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 980.0

25% 7.0 13.0 57.0 37.0 1013.0

50% 13.0 19.0 70.0 52.0 1018.0

75% 19.0 24.0 83.0 66.0 1022.0

max 130.0 87.0 100.0 100.0 1041.0

Pressure3pm Cloud9am Cloud3pm Temp9am Temp3pm Year \

count 128212.0 88536.0 85099.0 141289.0 139467.0 142193.0

mean 1015.0 4.0 5.0 17.0 22.0 2013.0

std 7.0 3.0 3.0 6.0 7.0 3.0

min 977.0 0.0 0.0 -7.0 -5.0 2007.0

25% 1010.0 1.0 2.0 12.0 17.0 2011.0

50% 1015.0 5.0 5.0 17.0 21.0 2013.0

75% 1020.0 7.0 7.0 22.0 26.0 2015.0

max 1040.0 9.0 9.0 40.0 47.0 2017.0

Month Day

count 142193.0 142193.0

mean 6.0 16.0

std 3.0 9.0

min 1.0 1.0

25% 3.0 8.0

50% 6.0 16.0

75% 9.0 23.0

max 12.0 31.0 2

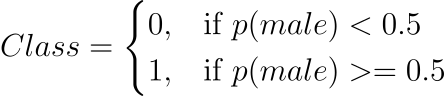

On closer inspection, we can see that the Rainfall, Evaporation, WindSpeed9am and WindSpeed3pm columns may contain outliers. I will draw boxplots to visualise outliers in the above variables.

|

|

Text(0, 0.5, 'WindSpeed3pm')

The above boxplots confirm that there are lot of outliers in these variables.

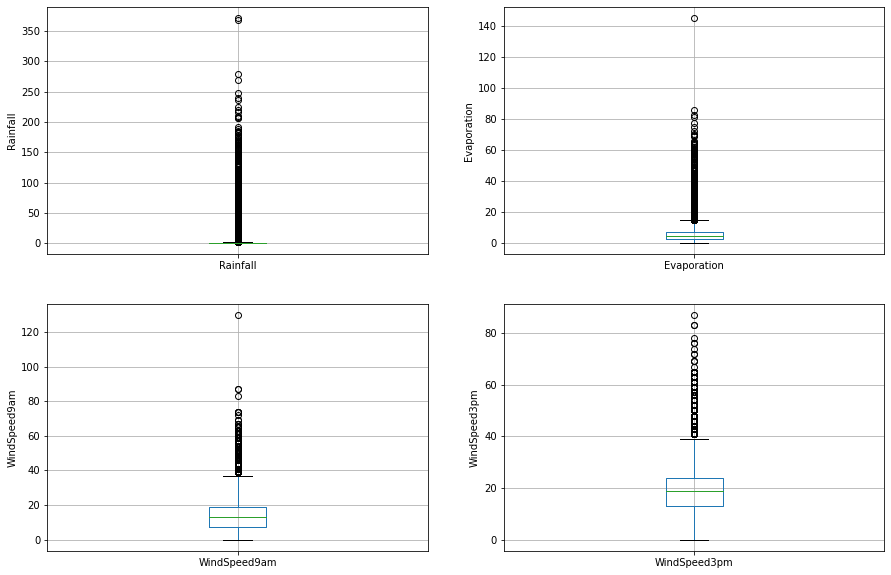

Check the distribution of variables

Now, I will plot the histograms to check distributions to find out if they are normal or skewed.

If the variable follows normal distribution, then I will do Extreme Value Analysis otherwise if they are skewed, I will find IQR (Interquantile range).

|

|

Text(0, 0.5, 'RainTomorrow')

We can see that all the four variables are skewed. So, I will use interquantile range to find outliers

|

|

Rainfall outliers are values < -2.4000000000000004 or > 3.2

For Rainfall, the minimum and maximum values are 0.0 and 371.0. So, the outliers are values > 3.2.

|

|

Evaporation outliers are values < -11.800000000000002 or > 21.800000000000004

For Evaporation, the minimum and maximum values are 0.0 and 145.0. So, the outliers are values > 21.8.

|

|

WindSpeed9am outliers are values < -29.0 or > 55.0

For WindSpeed9am, the minimum and maximum values are 0.0 and 130.0. So, the outliers are values > 55.0.

|

|

WindSpeed3pm outliers are values < -20.0 or > 57.0

For WindSpeed3pm, the minimum and maximum values are 0.0 and 87.0. So, the outliers are values > 57.0.

Multivariate Analysis

- An important step in EDA is to discover patterns and relationships between variables in the dataset.

- I will use heat map and pair plot to discover the patterns and relationships in the dataset.

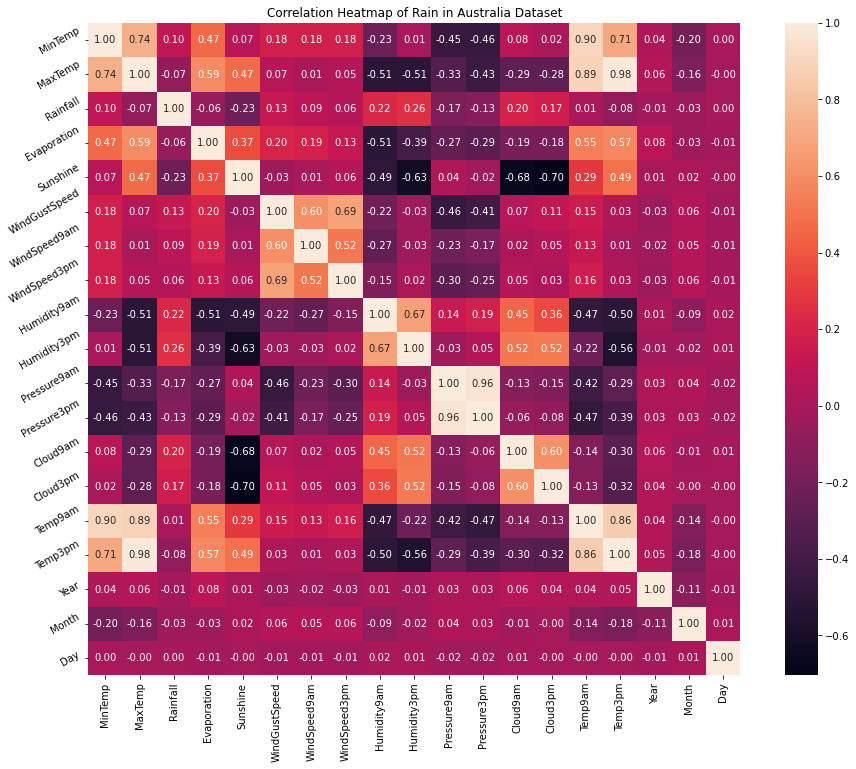

- First of all, I will draw a heat map.

|

|

Interpretation

From the above correlation heat map, we can conclude that :

- MinTemp and MaxTemp variables are highly positively correlated (correlation coefficient = 0.74).

- MinTemp and Temp3pm variables are also highly positively correlated (correlation coefficient = 0.71).

- MinTemp and Temp9am variables are strongly positively correlated (correlation coefficient = 0.90).

- MaxTemp and Temp9am variables are strongly positively correlated (correlation coefficient = 0.89).

- MaxTemp and Temp3pm variables are also strongly positively correlated (correlation coefficient = 0.98).

- WindGustSpeed and WindSpeed3pm variables are highly positively correlated (correlation coefficient = 0.69).

- Pressure9am and Pressure3pm variables are strongly positively correlated (correlation coefficient = 0.96).

- Temp9am and Temp3pm variables are strongly positively correlated (correlation coefficient = 0.86).

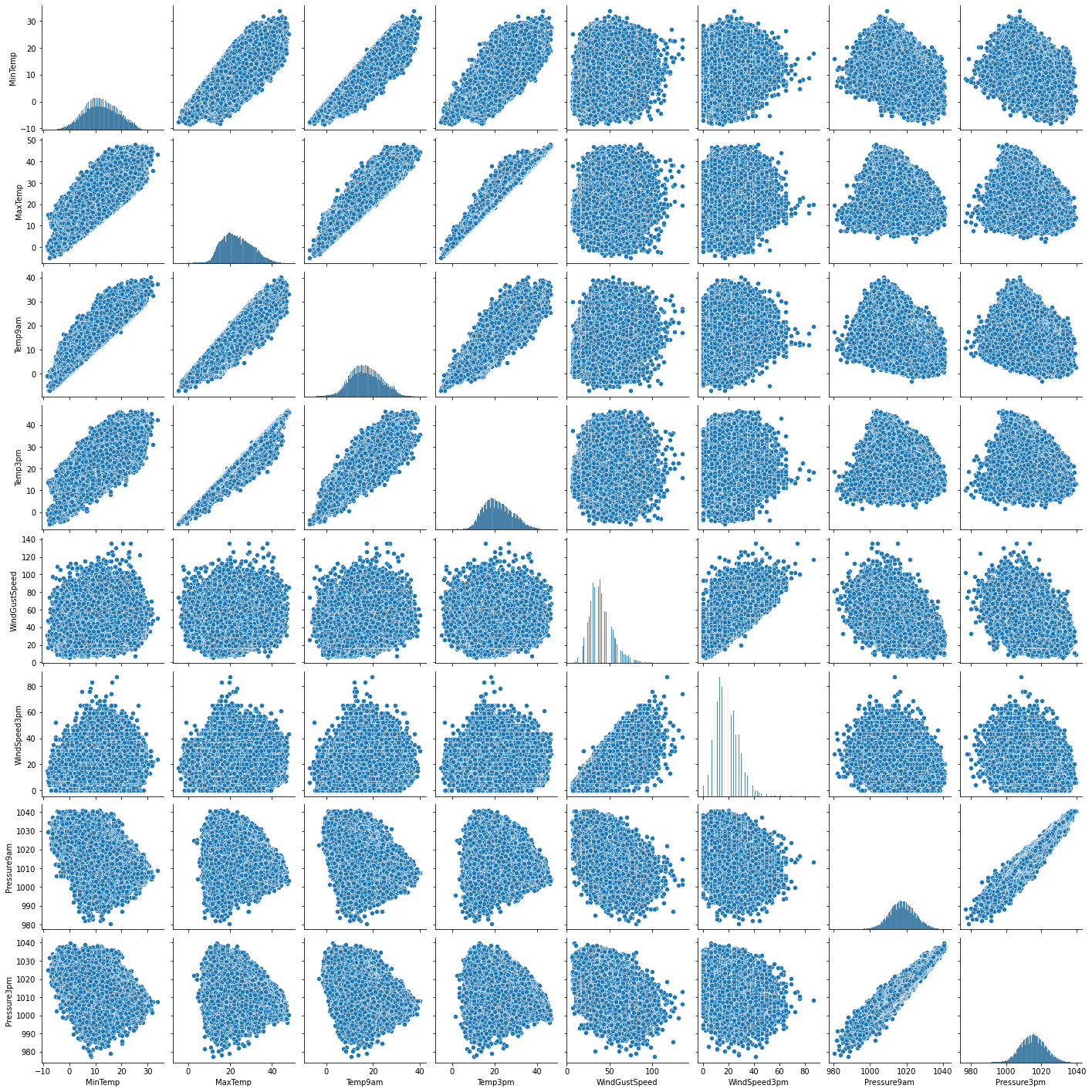

Pair Plot

First of all, I will define extract the variables which are highly positively correlated.

|

|

Interpretation

- I have defined a variable num_var which consists of MinTemp, MaxTemp, Temp9am, Temp3pm, WindGustSpeed, WindSpeed3pm, Pressure9am and Pressure3pm variables.

- The above pair plot shows relationship between these variables.

Split target from features

|

|

Feature Engineering

Feature Engineering is the process of transforming raw data into useful features that help us to understand our model better and increase its predictive power. I will carry out feature engineering on different types of variables.

Assumption

I assume that the data are missing completely at random (MCAR). There are two methods which can be used to impute missing values. One is mean or median imputation and other one is random sample imputation. When there are outliers in the dataset, we should use median imputation. So, I will use median imputation because median imputation is robust to outliers.

I will impute missing values with the appropriate statistical measures of the data, in this case median. Imputation should be done over the training set, and then propagated to the test set. It means that the statistical measures to be used to fill missing values both in train and test set, should be extracted from the train set only. This is to avoid overfitting.

|

|

|

|

MinTemp 0

MaxTemp 0

Rainfall 0

Evaporation 0

Sunshine 0

WindGustSpeed 0

WindSpeed9am 0

WindSpeed3pm 0

Humidity9am 0

Humidity3pm 0

Pressure9am 0

Pressure3pm 0

Cloud9am 0

Cloud3pm 0

Temp9am 0

Temp3pm 0

Year 0

Month 0

Day 0

dtype: int64

Engineering missing values in categorical variables

|

|

|

|

Location 0

WindGustDir 0

WindDir9am 0

WindDir3pm 0

RainToday 0

dtype: int64

Engineering outliers in numerical variables

We have seen that the Rainfall, Evaporation, WindSpeed9am and WindSpeed3pm columns contain outliers. I will use top-coding approach to cap maximum values and remove outliers from the above variables.

|

|

Encode categorical variables

|

|

|

|

We now have training and testing set ready for model building. Before that, we should map all the feature variables onto the same scale. It is called feature scaling. I will do it as follows

|

|

Now we can finally train the logistic regression model

Modelling

|

|

LogisticRegression(random_state=42, solver='liblinear')In a Jupyter environment, please rerun this cell to show the HTML representation or trust the notebook.

On GitHub, the HTML representation is unable to render, please try loading this page with nbviewer.org.

LogisticRegression(random_state=42, solver='liblinear')

|

|

predict_proba method

predict_proba method gives the probabilities for the target variable(0 and 1) in this case, in array form.

|

|

array([0.15163563, 0.703692 , 0.98254885, ..., 0.98586207, 0.9495434 ,

0.95416021])

|

|

array([0.84836437, 0.296308 , 0.01745115, ..., 0.01413793, 0.0504566 ,

0.04583979])

|

|

Model accuracy score: 0.8455

Compare the train-set and test-set accuracy

Now, I will compare the train-set and test-set accuracy to check for overfitting.

|

|

Training-set accuracy score: 0.8483

The training-set accuracy score is 0.8483 while the test-set accuracy to be 0.8455. These two values are quite comparable. So, there is no question of overfitting.

In Logistic Regression, we use default value of C = 1 (C is the inverse of regularization strength, regularization wasn’t discussed in this article, maybe in another article in the future). It provides good performance with approximately 85% accuracy on both the training and the test set. But the model performance on both the training and test set are very comparable. It is likely the case of underfitting.

I will increase C and fit a more flexible model.

|

|

LogisticRegression(C=100, random_state=42, solver='liblinear')In a Jupyter environment, please rerun this cell to show the HTML representation or trust the notebook.

On GitHub, the HTML representation is unable to render, please try loading this page with nbviewer.org.

LogisticRegression(C=100, random_state=42, solver='liblinear')

|

|

Training set score: 0.8488

Test set score: 0.8456

We can see that, C=100 results in higher test set accuracy and also a slightly increased training set accuracy. So, we can conclude that a more complex model should perform better.

Compare model accuracy with null accuracy

So, the model accuracy is 0.8501. But, we cannot say that our model is very good based on the above accuracy. We must compare it with the null accuracy. Null accuracy is the accuracy that could be achieved by always predicting the most frequent class.

So, we should first check the class distribution in the test set.

|

|

No 22098

Yes 6341

Name: RainTomorrow, dtype: int64

We can see that the occurences of most frequent class is 22098. So, we can calculate null accuracy by dividing 22098 by total number of occurences.

|

|

Null accuracy score: 0.7770

Interpretation

We can see that our model accuracy score is 0.8501 but null accuracy score is 0.7759. So, we can conclude that our Logistic Regression model is doing a very good job in predicting the class labels.

Now, based on the above analysis we can conclude that our classification model accuracy is very good. Our model is doing a very good job in terms of predicting the class labels.

But, it does not give the underlying distribution of values. Also, it does not tell anything about the type of errors our classifer is making.

We have another tool called Confusion matrix that comes to our rescue.

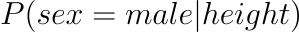

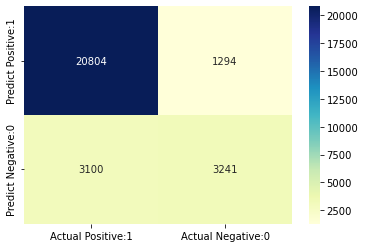

Confusion matrix

A confusion matrix is a tool for summarizing the performance of a classification algorithm. A confusion matrix will give us a clear picture of classification model performance and the types of errors produced by the model. It gives us a summary of correct and incorrect predictions broken down by each category. The summary is represented in a tabular form.

Four types of outcomes are possible while evaluating a classification model performance. These four outcomes are described below:

-

True Positives (TP) – True Positives occur when we predict an observation belongs to a certain class and the observation actually belongs to that class.

-

True Negatives (TN) – True Negatives occur when we predict an observation does not belong to a certain class and the observation actually does not belong to that class.

-

False Positives (FP) – False Positives occur when we predict an observation belongs to a certain class but the observation actually does not belong to that class. This type of error is called Type I error.

-

False Negatives (FN) – False Negatives occur when we predict an observation does not belong to a certain class but the observation actually belongs to that class. This is a very serious error and it is called Type II error.

These four outcomes are summarized in a confusion matrix given below.

|

|

Confusion matrix

[[20804 1294]

[ 3100 3241]]

True Positives(TP) = 20804

True Negatives(TN) = 3241

False Positives(FP) = 1294

False Negatives(FN) = 3100

The confusion matrix shows 20892 + 3285 = 24177 correct predictions and 3087 + 1175 = 4262 incorrect predictions.

In this case, we have

- True Positives (Actual Positive:1 and Predict Positive:1) - 20892

- True Negatives (Actual Negative:0 and Predict Negative:0) - 3285

- False Positives (Actual Negative:0 but Predict Positive:1) - 1175 (Type I error)

- False Negatives (Actual Positive:1 but Predict Negative:0) - 3087 (Type II error)

|

|

<AxesSubplot:>

Classification Metrices

Classification Report

Classification report is another way to evaluate the classification model performance. It displays the precision, recall, f1 and support scores for the model.

We can print a classification report as follows:

|

|

precision recall f1-score support

No 0.87 0.94 0.90 22098

Yes 0.71 0.51 0.60 6341

accuracy 0.85 28439

macro avg 0.79 0.73 0.75 28439

weighted avg 0.84 0.85 0.84 28439

|

|

Precision

Precision can be defined as the percentage of correctly predicted positive outcomes out of all the predicted positive outcomes. It can be given as the ratio of true positives (TP) to the sum of true and false positives (TP + FP).

So, Precision identifies the proportion of correctly predicted positive outcome. It is more concerned with the positive class than the negative class.

Mathematically, precision can be defined as the ratio of TP to (TP + FP).

|

|

Precision : 0.9414

Recall

Recall can be defined as the percentage of correctly predicted positive outcomes out of all the actual positive outcomes. It can be given as the ratio of true positives (TP) to the sum of true positives and false negatives (TP + FN). Recall is also called Sensitivity.

Recall identifies the proportion of correctly predicted actual positives.

Mathematically, recall can be given as the ratio of TP to (TP + FN).

|

|

Recall or Sensitivity : 0.8703

|

|

Specificity : 0.7147

f1-score

f1-score is the weighted harmonic mean of precision and recall. The best possible f1-score would be 1.0 and the worst would be 0.0. f1-score is the harmonic mean of precision and recall. So, f1-score is always lower than accuracy measures as they embed precision and recall into their computation. The weighted average of f1-score should be used to compare classifier models, not global accuracy.

Support

Support is the actual number of occurrences of the class in our dataset

|

|

array([[0.15163563, 0.84836437],

[0.703692 , 0.296308 ],

[0.98254885, 0.01745115],

[0.86912045, 0.13087955],

[0.61398609, 0.38601391],

[0.94498646, 0.05501354],

[0.95470402, 0.04529598],

[0.5290216 , 0.4709784 ],

[0.99863574, 0.00136426],

[0.78819565, 0.21180435]])

Observations

-

In each row, the numbers sum to 1.

-

There are 2 columns which correspond to 2 classes - 0 and 1.

- Class 0 - predicted probability that there is no rain tomorrow.

- Class 1 - predicted probability that there is rain tomorrow.

-

Importance of predicted probabilities

- We can rank the observations by probability of rain or no rain.

-

predict_proba process

- Predicts the probabilities

- Choose the class with the highest probability

-

Classification threshold level

- There is a classification threshold level of 0.5.

- Class 1 - probability of rain is predicted if probability > 0.5.

- Class 0 - probability of no rain is predicted if probability < 0.5.

|

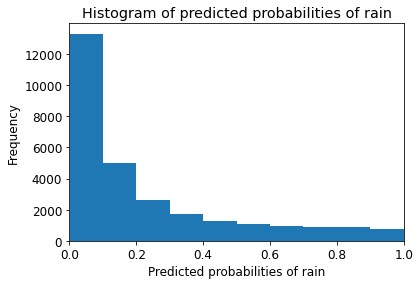

|

|

|

Text(0, 0.5, 'Frequency')

Observations

- We can see that the above histogram is highly positive skewed.

- The first column tell us that there are approximately 15000 observations with probability between 0.0 and 0.1.

- There are small number of observations with probability > 0.5.

- So, these small number of observations predict that there will be rain tomorrow.

- Majority of observations predict that there will be no rain tomorrow.

And that’s about it. Thank you for reading and see you in the next article!